A profitable business segment for a long time:

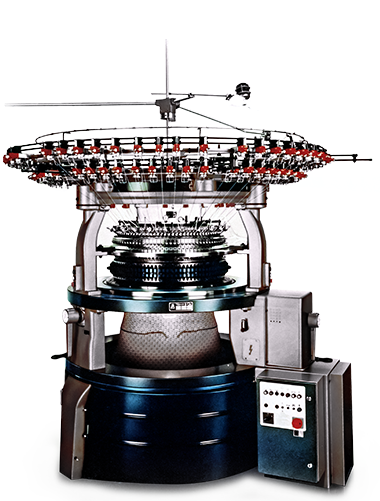

The advantages of Franke wire race bearings were particularly evident in circular knitting machines for the production of jersey fabrics.

In both the 1970s and 1980s, Franke faced serious economic challenges after decades of continuous growth. As tough as they were, they were overcome and used to better position the company for the future.

Since the mid-1960s, Franke had been steadily acquiring new customers from the textile machinery industry. The specially designed wire race bearings from Aalen were particularly sought-after for large circular knitting machines for the production of jersey fabrics. In 1967, the company even succeeded in acquiring the UK’s largest textile machinery manufacturer as a customer. From the early 1970s, the knitting machine industry developed into a “very eminent product field”, and Franke needed to respond. This was done in two ways: Firstly, production processes were changed towards more industrialised manufacturing. Secondly, the extra work caused by the flood of orders was covered by overtime.

It was a good strategy, as soon became apparent in 1974: New fashion trends brought the boom in jersey fabrics to an abrupt end – and with it the circular knitting machines. At Franke, the drop in sales of ball bearings for circular knitting machines in 1974 alone was an alarming 36 per cent. However, there was no danger for the company as a whole: Overtime was reduced, and in 1975 and 1976 there was a limited amount of short-time working. The loss of sales was then compensated for by new customers in the spinning machine sector and increasing orders in the newly created linear guide product area.

The second major economic challenge hit Franke in the 1980s. When orders for linear guides for the automotive industry in particular and the successful expansion of the sales network began to increase by leaps and bounds, while the delays in delivery could no longer be compensated for by overtime, Franke decided to build up new capacities. The machinery pool was expanded, as was the staffing level, and work was carried out in shifts for the first time. The boom ended in 1987. This was due to the falling dollar, a declining automotive market and a general economic downturn. Franke was forced to make drastic and painful cuts: For the first time in the company’s history, compulsory redundancies were announced in 1988. In addition, there were reshuffles and reorganisations, stocks were reduced, and long established rights were curtailed. The cost-cutting measures led to unprecedented uncertainty among employees – but also to a rapid resolution of the crisis. When the economy picked up again in 1989, Franke was well equipped for the next upturn because of this difficult transformation, especially as the textile machinery industry soon gained in importance again, which saw Franke attract new customers in the Asian markets. //